Submission - Joint submission to the 2007 Review of the Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) Code of Conduct to ASIC (May 2007)

- 1. Executive Summary

- 2. Marketplace Developments

- Q1 – What do you see as the emerging trends or developments in the consumer payments marketplace in Australia over the next few years?

- Q2 – Are there trends or developments that the Review Working Group should particularly consider in reviewing the EFT Code? What implications might these have for the regulatory scheme of the Code?

- Q3 – What are the issues associated with the emergence of 'non-contact’ payment facilities?

- 3. Growth in Online Fraud

- Q4 – What do you see as the main challenges in relation to online fraud over the next few years? Are there trends or developments that the Review Working Group should particularly consider in reviewing the EFT Code?

- Q5 – What information can you provide to the Working Group about online fraud countermeasures being considered or deployed by Australian financial institutions? How does the Australian response compare with that of other comparable countries, in your view?

- Q6 – Is the growth in, and growing publicity given to, fraud issues having an impact on online transacting in Australia at present?

- Q7 – What information can you provide to the Working Group about the online fraud mitigation skills of Australian online users?

- 4. Regulatory Developments

- 5. EFT Code, Part A (Scope and Interpretation)

- Q9 – Do you have any suggestions as to how the scope of Part A of the Code might be defined more simply? Should Part A include a non-exhaustive list of the main types of transactions to which it applies?

- Q10 – Should biller accounts continue to be excluded or should cl 1.4 be modified or, alternatively, removed altogether?

- Q11 – Do small businesses experience problems in relation to their banking services that need to be addressed? Does the EFT Code provide an appropriate framework for addressing any problems identified?

- 6. EFT Code, Part A (Requirements)

- Q12 – Should the requirement in cl 3.1 to provide written notification in advance of an increase in a fee or charge be replaced by another process? For example, should the notice appear in the national or local media on the day on which the increase starts?

- Q13 – Should cl 4.1(a) be revised to allow users to ‘opt-in’ to receive a receipt?

- Q14 – Should cl 4.1(a) be revised to deal with the problem of ATMs or other machines running out of paper for receipts? If so, how should it be amended?

- Q15 – Should cl 4.1(b)(v) be changed to allow a receipt for an EFT transaction by voice communication to specify the merchant identification number instead of the name of the merchant to whom the payment was made?

- Q16 – Should the EFT Code give more guidance on cl 4.1(a)(viii) regarding balance disclosure on receipts? If so, what guidance should be added?

- Q17 – Is there duplication or inconsistency between Part A of the EFT Code and the requirements of the Corporations Act that should be reviewed? How should any such issues be dealt with?

- Q18 – Are there aspects of the product disclosure regime under the Corporations Act that should be adopted as part of the regulatory framework under Part A of the EFT Code?

- Q19 – Should cl 7 be revised to specifically require subscribing institutions to identify and correct discrepancies between amounts recorded on the user’s electronic equipment or access method as transferred, and amounts recorded by the institution as received? What are your views on the suggested redrafting?

- Q20 – Should the EFT Code include a definition of the term ‘complaint’ under cl 10? If so, should it adopt the definition in AS ISO 10002–2006? Does the standard sufficiently address uncertainty about what is a complaint for the purposes of the EFT Code? Are there any other steps that might be taken to assist stakeholders to understand what is meant by a complaint under the Code?

- Q21 – Should AS ISO 10002—2006 become the required standard for internal complaint handling under the EFT Code?

- Q22 – Should account institutions be given a brief period within which to investigate a complaint before they must give the complainant written advice on how they investigate and handle complaints (as required under cl 10.3)? If so, what is an appropriate period?

- Q23 – Should any changes be made to the timeframe for resolving complaints under cl 10 of the EFT Code?

- Q24 – Do you have information or views about the level of compliance with cl 10?

- Q25 – Has the procedure in cl 10.12 been an effective incentive to compliance? Are further incentives required, and if so what form should they take?

- Q26 – Should the EFT Code be amended to cover situations when the subscribing institution is unable to, or fails to, give the dispute resolution body a copy of the record within a certain time? If yes, should the Code specify that a dispute resolution body is entitled to resolve a factual issue to which a record relates on the basis of the evidence available to it?

- Q27 – Should there be a time after which EFT Code subscribers are no longer required to resolve complaints about EFT transactions on the basis set out in Part A of the Code?

- 7. EFT Code, Part A (Liability)

- Q28 – Should account holders be exposed to any additional liability under cl 5 for unauthorised transaction losses resulting from malicious software attacks on their electronic equipment if their equipment does not meet minimum security requirements? Do the benefits and costs of extending account holder liability justify such an extension of cl 5? What implementation issues would have to be addressed?

- Q29 – Should an additional example be included in cl 5.6(e) specifically referring to the situation when an account user acts with extreme carelessness in responding to a deceptive phishing attack?

- Q30 – Apart from this possible clarification, should account holders be exposed to any additional liability under cl 5 for unauthorised transaction losses because of a deception-based phishing attack? Do the benefits and costs of extending account holder liability justify such an extension? What implementation issues would have to be addressed?

- Q31 – To what extent has the restriction on using a user’s name or birth date under cl 5.6(d), been relied on?

- Q32 – Should the restriction on users acting ‘with extreme carelessness in failing to protect the security of all the codes’ under cl 5.6(e) be further elaborated or extended in some way? Should additional examples of extreme carelessness be given?

- Q33 – Should the EFT Code specifically address the situation when an unauthorised transaction occurs after a user inadvertently leaves their card in an ATM machine?

- Q34 – To what extent is unreasonable delay in notification of security breaches by account users currently an issue? Please provide on the frequency and cost of such delays, if possible. (You may wish to provide this information on a confidential basis.)

- Q35 – Should the circumstances when the account holder is liable on the basis of unreasonably delayed notification under cl 5.5(b) be extended to encompass unreasonable delay in notifying online security breaches of which the user becomes aware?

- Q36 – Should the standard of ‘unreasonably delaying notification’ under cl 5.5(b) be replaced by a specific time after which the account holder is liable? What would be an appropriate time, if such a change were introduced?

- Q37 – To what extent do subscribing institutions currently use the other ‘no fault’ liability provision in cl 5.5(c)?

- Q38 – Is there a case for increasing the current ‘no fault’ amount of $150? If so, on what basis and what should the new amount be?

- Q39 – Should subscribers prohibit in their merchant agreements the practice of taking customers’ PINs or other access codes as part of a ‘book up’ arrangement? If so, should this be subject to any exceptions; and, if it should, what should those exceptions be?

- Q40 – Should cl 6 be reformulated to clarify that the subscribing institution is liable for any failure resulting from equipment malfunction when they have agreed to accept instructions through that equipment?

- Q41 – To what extent, and how, should the Code address the issue of mistaken payments? Discuss the usefulness, practicality and cost of implementing some or all of the measures outlined, as well as any other measures you consider appropriate.

- 8. EFT Code, Part B (Scope and interpretation)

- Q42 – Should the scope of Part B of the EFT Code continue to be defined by reference to the concepts of ‘stored value facilities’ and ‘stored value transactions’ as at present; or should a different approach be taken? What issues are raised by possible alternative approaches?

- Q43 – Assuming the scope of Part B of the EFT Code continues to be defined in terms of the concepts of 'stored value facilities' and 'stored value transactions', what changes, if any, should be made to the definitions and other provisions of cl 11?

- 9. EFT Code, Part B (Obligations)

- Q44 – Should any changes or additions be made to cl 14?

- Q45 – Should operators of facilities regulated under Part B be required to make a transaction history for the facility available on request for a specified period?

- Q46 – Are any aspects of Part B of the EFT Code incompatible with the requirements of the Corporations Act? How should any incompatibility be addressed?

- Q47 – Should the rights to exchange stored value under cl 15 be narrowed?

- Q48 – Should the EFT Code include a requirement that all prepaid facilities regulated by Part B must have a minimum use time (i.e. the time before value expires) of at least 12 months?

- Q49 – Should the EFT Code include a requirement that the use period or date be displayed on any physical device (such as a card) used to make payments in connection with a prepaid facility?

- Q50 – Should the right to a refund of lost or stolen stored value under cl 16 only be mandated for facilities that allow more than a certain amount of value to be prepaid? If so, what should the minimum amount be?

- Q51 – Should there be a requirement that regulated facilities over a certain value include a mechanism (such as PIN security) that allows users to control access to the available value on the facility?

- Q52 – Should the use of unilateral variation clauses in the terms and conditions for facilities regulated under Part B be restricted?

- Q53 – Should the complaint investigation and dispute resolution regime under cl 10 of the EFT Code apply without limitation to Part B facilities and transactions under cl 19?

- Q54 – Should Part B of the EFT Code address the issue of payment finality?

- 10. EFT Code, Part C (Privacy and electronic communications)

- Q55 – Should the provisions about privacy under cl 21 be modified and/or extended to cover other areas or issues?

- Q56 – Should the status of the cl 21.2 guidelines be changed to make these provisions contractually binding requirements?

- Q57 – Should the EFT Code require that transaction receipts include only a truncated version of the account number?

- Q58 – Should the EFT Code require that transaction receipts not include the expiry date and/or other information that is not required for transaction confirmation purposes?

- Q59 – What would be the cost of implementing the suggested changes? Are there any implementation issues that should be considered? What would be an appropriate implementation timeframe?

- Q60 – Should cl 22.1(b)(ii) be deleted or amended in some way?

- Q61 – Should cl 22.2(b)(ii) be deleted or amended in some way?

- Q62 – Should changes be made to the EFT Code to address issues associated with products that only allow electronic communication of account information? If so, what changes should be made?

- Q63 – Should the EFT Code address the situation when an account institution receives a mail delivery failure message after sending a communication mandated under cl 22? If so, what approach should be adopted? How is this situation currently handled?

- 11. EFT Code, Part C (Administration and review)

- Q64 – Should ASIC continue to be primarily responsible for administering the EFT Code? Are there other arrangements that should be considered?

- Q65 – Should the EFT Code allow its requirements to be modified in certain circumstances? If so, what modification powers should be included and how should they be administered?

- Q66 – How should compliance be monitored? What alternatives to the current self-reporting survey should be considered?

- Q67 – How should the EFT Code be reviewed? What alternatives to the current approach should be considered?

- 12. Other issues from ASIC Consultation Paper

- Q68 – In your view, why has membership of the EFT Code remained limited generally to providers of generic banking services?

- Q69 – What steps could/should be taken to broaden EFT Code membership?

- Q70 – How much of the EFT Code’s requirements do non-subscribing entities take into account even though they do not subscribe to it?

- Q71 – What changes could/should be made to the way the EFT Code is written, designed and presented to make it a more user friendly and accessible document?

- Q72 – Should the EFT Code include a statement of objectives? If so, what should the objectives of the EFT Code be?

- 13. Additional Consumer Issues

- 14. Appendix 1 – Authentication Technologies

- Attempts to Strengthen Two-factor Authentication

- Tricerion Strong Mutual Authentication

- Secure Remote Password Protocol

- Delayed Password Disclosure

- Federated Identity Management Systems

- Challenge/Response Mechanisms

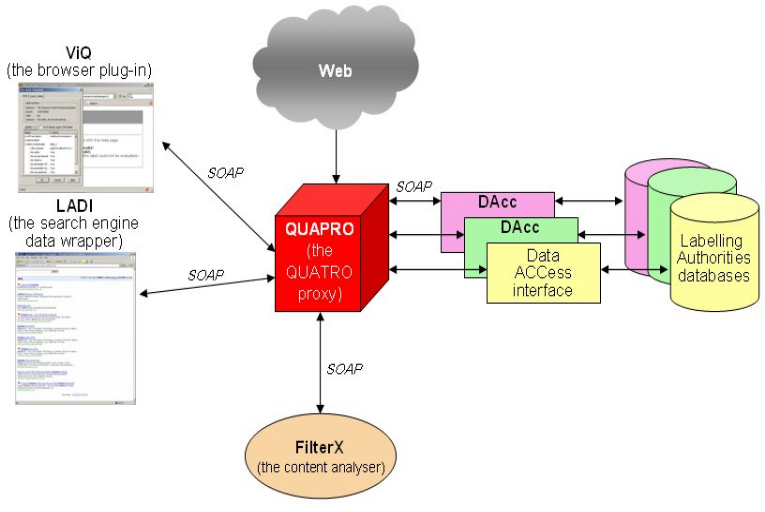

- QUATRO

- GeoTrust True Site

- Petname

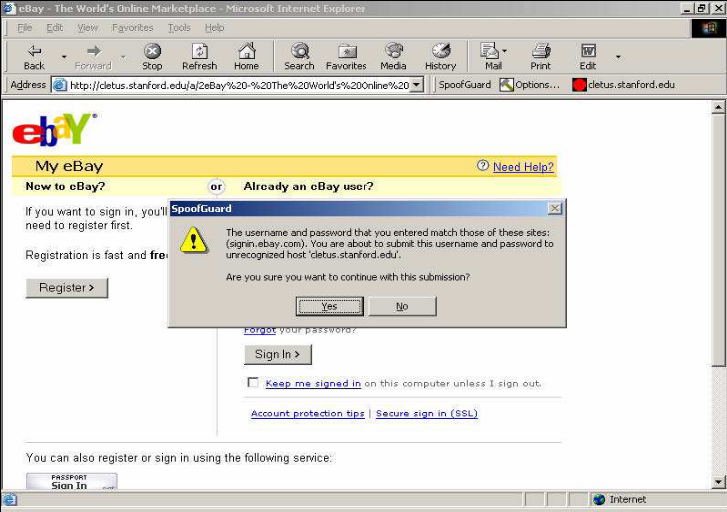

- SpoofGuard

- Trusted Password Windows and Dynamic Security Skins

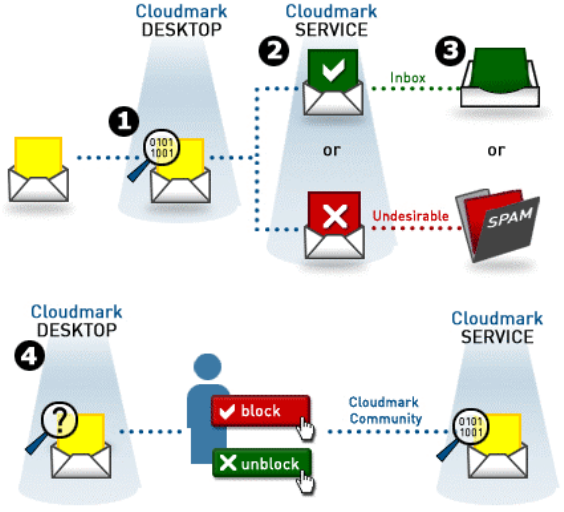

- Cloudmark Network Feedback System

- 15. Appendix 2 – Resources

![]()

Joint submission to the 2007 Review of the Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) Code of Conduct

CHOICE

Consumer Action Law Centre

Centre for Credit and Consumer Law

(30 May 2007)

Prepared by: Galexia

Suite 95 Jones Bay Wharf, 26-32 Pirrama Road,

Pyrmont (Sydney) NSW 2009, Australia

ACN: 087 459 989

Ph: +61 2 9660 1111

Fax: +61 2 9660 7611

WWW: www.galexia.com

![]()

Document Control

Client

This report has been written for CHOICE, the Consumer Action Law Centre and the Centre for Credit and Consumer Law.

Document Purpose

This document is a joint submission to the 2007 Review of the Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) Code of Conduct from CHOICE, the Consumer Action Law Centre and the Centre for Credit and Consumer Law.

Document Production

This Document was prepared by Galexia. Guidance, input and comments were received from a small reference group consisting of representatives of CHOICE, the Consumer Action Law Centre, the Centre for Credit and Consumer Law, the Australian Privacy Foundation, the Consumer Credit Legal Centre (NSW), Care Inc. Financial Counseling Service and Consumer Law Centre of the ACT. Funding assistance was received from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Consumer Advisory Panel (ASIC CAP).

Consultant Contact: Chris Connolly (Director)

Galexia

Suite 95 Jones Bay Wharf

26-32 Pirrama Road, Pyrmont NSW 2009

Phone: +612 9660 1111

Fax: +612 9660 7611

Copyright

Copyright © 2007 Galexia, CHOICE, Consumer Action Law Centre and Centre for Credit and Consumer Law.

1. Executive Summary

This document is a joint submission from CHOICE, the Consumer Action Law Centre and the Centre for Credit and Consumer Law to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission in respect of the 2007 Review of the Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) Code of Conduct.

This Document was prepared by Galexia. Guidance, input and comments were received from a small reference group consisting of representatives of:

- CHOICE;

- Consumer Action Law Centre;

- Centre for Credit and Consumer Law;

- Australian Privacy Foundation;

- Consumer Credit Legal Centre (NSW); and

- Care Inc. (Financial Counseling Service and Consumer Law Centre of the ACT).

Funding assistance was received from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Consumer Advisory Panel (ASIC CAP).

As ASIC would be aware, many consumer and community groups have limited resources to participate in reviews of this size and import. With greater resourcing capacity, it might have been possible for other organisations to have also had a direct input into the preparation of this submission.

Consumer stakeholders see this review as an opportunity to dramatically improve the EFT Code. This submission attempts to answer every question raised in the ASIC Consultation paper and also provides additional comments and suggestions.

The core of this submission is a proposed five-step approach to improving the Code:

Step 1: Retaining a fair liability approach

The current liability approach in Clause 5 of the Code is working well. Although there have been some changes in the vulnerability of Internet banking since the last review of the Code (for example the growth in social engineering attacks), there is no justification for changing the overall liability regime in the Code. Financial institutions remain in the best position to address security issues in Internet banking and the responsibility of consumers is already fairly addressed in the Code.

Two key suggested liability reforms are firmly rejected in this submission:

- Increased liability for consumers who fail to secure their personal computers

This submission presents detailed arguments outlining policy and practical issues which would be faced if this reform was to proceed. - Increased liability for consumers who respond to social engineering attacks

Although there are measures that can be taken by banking customers in order to combat phishing attacks, this submission describes how these measures are considerably less effective than the technologies that can be utilised by financial institutions to deal with phishing.

Step 2: Improving the dispute resolution experience for consumers

This submission presents some suggested improvements to ensure internal and external dispute resolution processes are meeting the needs of consumers. Reference is made to the Consumer Caseworker Submission which contains detailed case studies of EFT related complaints. This submission endorses the recommendations contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Step 3: Shortening the Code

The Code has become long and unwieldy and this is having a negative impact on Code subscription, compliance, education and complaints management. Code length has a knock on impact on the length of terms and conditions as all clauses tend to be repeated by financial institutions in their terms and conditions – making them difficult to digest for consumers.

This submission recommends some significant changes to the Code in the interest of shortening the Code:

- The complete removal of Part B of the Code;

- Moving specific scenarios set out in the text to examples in notes rather than including them all as separate Clauses in the Code, and relying on common sense interpretation by internal and external dispute resolution; and

- The removal of a number of minor Clauses (described in further detail in the submission).

Step 4: Simplifying the Code

The Code has become complex and difficult to interpret. This is having a negative impact on Code subscription and complaints management. Code complaints often relate to small value transactions and it is difficult to justify the expense of legal advice in interpreting the Code. Simplifying the Code will benefit all stakeholders.

This submission recommends some significant changes to the Code in the interest of simplifying the Code:

- Removal of the business / consumer account distinction so that the Code can be more simply applied to all transactions. This will simplify terms and conditions, implementation, complaints management and data collection;

- Removal of Part B from the Code will simplify the Code. Part B is technically complex and has delivered little benefit;

- Removal of Part B and the collapse of Part A and Part C into one section will simplify the Code. There will be no requirement to refer to ‘Parts’ in the text;

- Relocation of endnotes to short footnotes so that they can be read together with the text; and

- Relocation of all Clauses on interpretation and scope into one section at the front of the Code (e.g. moving Clauses 8 and 20 to the beginning of the Code).

Step 5: Commissioning a Technology Neutrality Review of the final Code text

In addition to reviewing the Code content, this submission recommends a thorough Technology Neutrality Review of the Code text. This review should ensure that the terms used in the Code are defined broadly enough to encompass the wide range of technology that might be used to complete an EFT transaction. The key terms that require review are:

- Electronic equipment;

- Device;

- Identifier; and

- Code.

This issue is discussed in further detail in response to Q73 – Are there other issues not covered in this consultation paper that the review should address? below.

2. Marketplace Developments

Q1 – What do you see as the emerging trends or developments in the consumer payments marketplace in Australia over the next few years?

Three emerging trends in the marketplace are of interest in relation to the EFT Code review:

- 1. Growth in use of third party direct electronic transfers

Internet banking appears to have entered a new phase where it is common for customers to arrange direct transfer of funds to a third party using their BSB and Account Number. This service is now offered for all accounts – whereas at the time of the last review of the EFT Code this service was only available for a small number of account holders. Some financial institutions require additional security or authentication for direct transfers (e.g. there may be an extra security question before the transfer is confirmed). - 2. Emergence of new Internet only payment services

A small number of new, Internet based payment systems are operating. Two of these services – PayPal and Checkout – have become quite prevalent and are widely used in Australia. They are not traditional payment systems or financial institutions but they do share many characteristics with credit cards and Internet banking. This type of service was not in widespread use at the time of the last EFT Code review. - 3. Convergence / confusion of consumer banking and business banking

Although this development was also considered during the previous review of the EFT Code, there appears to now be even greater convergence of consumer banking and business banking. This is due to the growth in the home business and micro business sectors, and the need for micro-businesses (e.g. eBay sellers) to offer electronic payment systems to consumers. It is unlikely that all home businesses and micro businesses operate a strict division between their personal banking and their business banking, so determining which accounts are personal accounts may be difficult.

Q2 – Are there trends or developments that the Review Working Group should particularly consider in reviewing the EFT Code? What implications might these have for the regulatory scheme of the Code?

The convergence / confusion of consumer banking and business banking has significant implications. This issue is important because financial institution terms and conditions continue to be considerably harsher for those accounts not protected by the EFT Code. Terms and conditions provided by financial institutions are currently divided into Code compliant and non-compliant sections depending on the ‘business’ nature of the transaction. This issue may also have implications for the complexity of dispute resolution processes.

Q3 – What are the issues associated with the emergence of 'non-contact’ payment facilities?

This does not appear to be a significant issue at this time. However, two minor issues may be raised by non-contact payment facilities:

- Privacy

Non-contact payment systems are not widespread and appear to be limited to stored value applications in the transport sector where their speed and convenience is appreciated by consumers. However, privacy and security issues may emerge if applications combine non-contact products with higher risk personal information (i.e. if the product can be accessed without authorisation and valuable personal information is revealed.). We note, for example, that this issue was a particular concern during the upgrading of passports to include non-contact functionality. - Absence of a PIN or Password

Non-contact payment facilities may, in some circumstances, result in an electronic transfer without use of a PIN, password or other code. However, this does not appear to be an issue that requires detailed consideration in the Review of the EFT Code at this stage.

3. Growth in Online Fraud

Q4 – What do you see as the main challenges in relation to online fraud over the next few years? Are there trends or developments that the Review Working Group should particularly consider in reviewing the EFT Code?

There has been steady growth in the sophistication of fraud and this is matched by rising complexity in preventing fraud.

Fraud can take place through a variety of technical and social engineering techniques designed to compromise communication channels used to exchange sensitive data or to coax consumers into disclosing this data.

These techniques are constantly evolving. Some common forms include:

- Phishing

Phishing involves the use of socially engineered (‘spoofed’) websites that are designed to appear as if they belong to legitimate and reputable businesses and financial institutions.[1] Users are lured to these websites by congruently designed emails. Once at the spoofed website, the user is deceived into providing confidential data such as usernames and passwords. - Pharming

Pharming occurs when a fraudulent party interferes with the domain name resolution process used to map a URL requested by an Internet user to its corresponding IP address. Pharming typically takes one of two forms:- Firstly, a DNS server can be hijacked and its data modified such that when a user enters the URL of a legitimate organisation’s website, the server maps the domain name to the IP address of a spoofed website which the user is then forwarded to.[2]

- The second form of pharming relies on the fact that end-user computers typically store a hosts file containing the IP addresses of certain commonly accessed domains. The hosts file abrogates the need for a DNS server to be contacted when the user wishes to visit those domains. A fraudulent party can, in some circumstances, compromise the data in the hosts file so that it points to the IP address of a spoofed website.[3]

- Man-in-the-middle (MITM)

Man-in-the-middle attacks take place where a fraudulent party is able to intercept online communications between two innocent parties (such as a website and an end-user). Such attacks may be facilitated through the sending of deceptive emails which contain a link to a proxy server monitored by the fraudulent party. The proxy server undertakes the task of routing communications between the end-user and the actual website the user intends to deal with. Since all communications are routed via the proxy, the fraudulent party is able to covertly read and modify communications made between the website and end-user. - Replay Attacks

A replay attack is an extension of the conventional MITM attack in which the fraudulent party uses data they have obtained by eavesdropping on the communications between the website and end-user to assume the identity of either at a later date. - Spyware

Spyware refers to software covertly installed on an end-user’s machine that then proceeds to monitor and collect information about the user’s activities. More malignant versions may perform tasks such as redirecting users and stealing confidential information belonging to the user and distributing it to fraudulent parties. Common forms of spyware include keystroke loggers, screen loggers and pop-up window generators. Despite the availability of software utilities to detect and remove many types of spyware, it has become an extremely troublesome issue for Internet users. A 2004 survey of US Internet users revealed that 80% of respondents’ computers were infected with spyware, with close to 90% of those respondents being unaware of the spyware’s presence. Another study found that 85 million spyware programs were installed on the computers of a sample of Internet users, a clear indication of the magnitude of the problem.[4]

The increasing frequency with which these various attacks have begun to occur has precipitated a need for Internet users to be able to reliably verify the identity of websites they are visiting and the integrity of communications channels they use to communicate with web servers. In response to this need, a variety of authentication approaches have been proposed and/or developed. These are discussed further in the response to Question 30 (Potential Responses to Phishing Attacks and other forms of Online Fraud).

In reviewing the EFT Code, the Working Group should consider the fact that financial institutions are in the best position to implement many of these authentication technologies. This is a factor which largely undermines suggestions that the liability of account holders for losses resulting from online fraud should be increased compared with the current version of the Code.

Q5 – What information can you provide to the Working Group about online fraud countermeasures being considered or deployed by Australian financial institutions? How does the Australian response compare with that of other comparable countries, in your view?

There is no established industry recommendation or mandate which specifically requires Australian financial institutions to implement authentication technologies that are more advanced than the conventional username and password approach. However, several Australian banks (including Commonwealth Bank,[5] National Australia Bank,[6] Bendigo Bank,[7] ANZ,[8] Westpac[9] and HSBC[10]) have implemented some form of two-factor authentication for their Internet banking services.

However, two-factor authentication provides only minimal protection against phishing attacks.[11] For this reason, financial institutions need to consider deploying technologies that enable them to authenticate their websites to customers.

Nevertheless, there are examples of recommendations and mandates being issued in other jurisdictions regarding the use of two-factor authentication by financial institutions. These include:

- United Kingdom

APACS, the UK trade association for payments and for institutions who deliver payment services to customers, currently has 31 members whose payment traffic volumes account for 97% of the total UK payments market.[12] APACS is working with a number of UK banks on a trial to implement a form of two-factor authentication known as ‘remote card authentication’. Using this form of authentication, account holders seeking to use Internet banking services must first swipe their card through a hand-held reader provided by their bank, and then enter their PIN. Once the bank has confirmed the PIN is correct, the account holder is provided with a dynamically generated passcode which they then use to log in. It is expected the trial will commence at some stage in 2007.[13] - United States

The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) is empowered to establish principles and standards for US financial institutions.[14] In October 2005, the FFIEC released a guidance document for financial institutions regarding authentication mechanisms necessary for the verifying the identity of customers who access online financial services. The document states that financial institutions should implement effective methods of authentication that are commensurate with the risk associated with online banking. The FFIEC states that it does not consider single-factor authentication sufficient in circumstances where transactions are high-risk,[15] which would appear to cover Internet banking transactions. US financial institutions were expected to have conformed with the requirements of the guidance documents by the end of 2006.[16]

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), an independent agency of the US federal government, has also recommended that financial institutions consider deploying two-factor authentication in response to the increased incidence of online fraud.[17] - Hong Kong

In May 2005 the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Hong Kong Police Force and Hong Kong Association of Banks jointly announced that banks would make two-factor authentication mechanisms available to customers engaging in high-risk Internet transactions.[18] - Singapore

The Monetary Authority of Singapore has released risk management guidelines for financial institutions. The guidelines advocate the use of two-factor authentication as a means of combating online fraud.[19]

Q6 – Is the growth in, and growing publicity given to, fraud issues having an impact on online transacting in Australia at present?

Online fraud is undoubtedly becoming an increasingly prominent form of identity theft. For example, the Anti-Phishing Working Group (APWG), a worldwide association consisting of over 2600 members (including several prominent financial institutions) received 23 610 reports of phishing attempts on the Internet during February 2007, representing an increase of more than 12 000 compared with the corresponding figure for the same month in 2006.[20] Of particular interest is that of the 16 463 unique phishing websites detected by the APWG during February 2007, over 92% of those sites attempted to falsely identify themselves as belonging to organisations in the financial services industry.[21] This emphasises the necessity for financial institutions to improve their response to the problem of online fraud being perpetrated against their customers.

APACS, the UK trade association for payments and for institutions who deliver payment services to customers, reported that in the first six months of 2006, incidences of online fraud caused the loss of 22.5 million pounds (approximately $54.5 million AUD), representing an increase of 55% compared with the corresponding period in 2005.[22]

The Australian Payments Clearing Association (APCA) has also reported that there were 37 952 incidents of card-not-present fraud (which includes online fraud) perpetrated in Australia on Australian-issued cards during the period from July 2005 to June 2006, with a total value of over eleven million Australian dollars. There were also over 38 000 incidents of card-not-present fraud relating to cards issued outside of Australia with a total value of over ten million Australian dollars.[23] Given the growing incidence of phishing attacks worldwide, it is realistic to expect these already significant figures will continue to rise at a rapid rate. If more is not done by financial institutions to control the growth of online fraud, this will undoubtedly affect the confidence of their customers in using the online channel to perform banking transactions and hence the continued viability of online banking generally.[24]

The fragile nature of consumer confidence in Internet banking and electronic payment systems in Australia appears to be resulting in some financial institutions using phrases such as ‘we guarantee the security of your money’ on Internet banking sites. However, such a claim is usually accompanied by a considerable degree of fine print.

A small selection of ‘guarantees’ are included in the following table:

|

Institution |

Claim |

CBA |

The Commonwealth Bank’s Security Guarantee The Commonwealth Bank’s Security Guarantee guarantees the safety of your money as long as you keep to the NetBank terms and conditions. |

Westpac |

Our Security Guarantee Subject to investigation, we guarantee that you will not be personally liable for any unauthorised transactions on your Westpac accounts, provided that you: Were in no way responsible for the unauthorised transaction Did not contribute to the loss Complied with the Westpac Internet Banking terms and conditions |

ANZ |

Our guarantee to ANZ Internet Banking customers When you do your banking with ANZ Internet Banking, we have security measures in place designed to protect your transactions. You will be protected against unauthorised transactions carried out on your account as a result of using ANZ Internet Banking where you have complied with the Electronic Banking Conditions of Use and it is clear that you have not contributed to the loss. |

St George |

Our guarantee: St. George Secure In the unlikely event that an unauthorised transaction does occur on your account, we will refund the full amount. Read more about our commitment to you. (This link then leads to further qualifications but they don’t appear on the home page) |

The lesson from the use of these ‘guarantees’ in Internet banking promotional literature is that financial institutions need to convince consumers that they can use Internet banking with confidence. Reliance on these guarantees is conditional on the underlying terms and conditions and subsequently on the standards imposed by the EFT Code.

Q7 – What information can you provide to the Working Group about the online fraud mitigation skills of Australian online users?

There does not appear to be any data readily available on this issue in Australia. Fraud mitigation skills are likely to be extremely low in the general population due to the complex and sophisticated nature of both Internet fraud and suggested remedies. There may also be large pockets of the community where general awareness levels in relation to fraud are very low.

4. Regulatory Developments

Q8 – Are there developments in the regulatory environment that the Review Working Group should particularly consider? What are the implications of those developments for the EFT Code?

Although there has not been time to consider this question in detail, there are several regulatory developments that may be relevant:

- Review of privacy legislation by the Australian Law Reform Commission.

- Productivity Commission review of Australia’s Consumer Policy Framework.

Both reviews have a focus on the simplification and harmonisation of regulation in Australia.

5. EFT Code, Part A (Scope and Interpretation)

Q9 – Do you have any suggestions as to how the scope of Part A of the Code might be defined more simply? Should Part A include a non-exhaustive list of the main types of transactions to which it applies?

The definition of scope in Part A appears to remain sufficiently broad enough to cover all target transactions. However, the drafting might be improved if the entire scope was described in Clause 1.1 without any need to refer to later provisions (e.g. 1.3 and 1.4).

Also, Clause 1.1 (B) appears to include a substantive regulatory requirement rather than a statement of scope – in that it requires financial institutions to be responsible for the actions of some third party providers. This Clause has always appeared out of place in a scope section.

A further issue relates to the definitions of some terms. These may need to be reviewed to ensure technology neutrality is maintained. One issue here is that modern access methods now include two-factor authentication approaches resulting in a plethora of new devices – smart cards, one-time password generators, mobile phones, USB tokens – all of which might play a role in providing access.

As a result, some of the definitions (e.g. ‘device’ and ‘electronic equipment’) may need to be reviewed for technology neutrality. Some initial observations show the complexity of these definitions in practice:

- A mobile phone is currently defined as both a device and electronic equipment.

- The definition of code means that it must be known to the user, but modern codes (e.g. one-time passwords) are generated by devices and only ‘known’ to the consumer for a short period.

It may be useful to conduct a thorough Technology Neutrality Review of the definitions in the Code once other clauses are agreed in the Review process.

Q10 – Should biller accounts continue to be excluded or should cl 1.4 be modified or, alternatively, removed altogether?

The reasons for the current exclusion of Biller accounts are unclear. It is preferable to have the coverage of the Code be as broad and simple as possible and the biller exemption has already caused some confusion. Biller accounts are growing in popularity and the exclusion should be removed to ensure that all EFT transactions receive equal treatment.

Q11 – Do small businesses experience problems in relation to their banking services that need to be addressed? Does the EFT Code provide an appropriate framework for addressing any problems identified?

It is essential that in this Review of the EFT Code the distinction between consumer and business transactions in the Code should be removed. This issue was the source of considerable debate during the last Review and it is arguable that the convergence of consumer and business banking has only increased since then. It is now very difficult to distinguish between consumer and business transactions.

There are no policy reasons for not including businesses in a Code that addresses mainly technical issues. Some arguments are presented in the Consultation paper, but they each have clear weaknesses:

- Argument 1: Small businesses must be given incentives to maintain and improve their systems

This argument implies that small business must be exposed to losing money via Internet banking fraud as a lesson in security management. In fact, financial institutions receive significant benefits from small businesses migrating to Internet banking from more expensive branch banking, and exposure to losses from fraud provides no incentive at all to improve the security of small business computer systems as they are in a weaker position than financial institutions when it comes to preventative measures. - Argument 2: The volume and value of business transactions may expose financial institutions to higher average losses

This argument fails to recognise that average losses are in direct proportion to daily transaction limits and are not a reflection of the liability provisions. Although overall volume may be higher, income from business banking is also very high and the benefits to financial institutions of attracting more businesses to use Internet banking should still significantly outweigh the risks of including businesses in the EFT Code. - Argument 3: Subscribers may demand a reduction in the overall level of protection to the detriment of consumer stakeholders.

Relief of the confusion over the distinction between consumer and business banking will benefit all stakeholders, including financial institutions, and this benefit is likely to outweigh any perceived detriments from this change. The threat to one group of stakeholders (consumers) appears hollow in this context.

It is also interesting to consider the terms and conditions currently provided by financial institutions. Typically, they are divided into Code compliant and non-compliant sections depending on the ‘business’ nature of the transaction. The non-compliant provisions can be harsher than the compliant provisions – particularly in relation to liability and dispute resolution.

Current terms and conditions also have specific and sometimes peculiar differences between liability for business customers and non-business customers. For example, one bank makes business consumers liable if they use part of their Driver Licence Number as their passcode, but they apply the EFT Code tests (name and birth date) to personal customers. However, a driver’s licence has no particular relevance to a business transaction. It is clear that financial institutions simply extend harsher terms to those customers not protected by the EFT Code, without any reference to the ‘business’ nature of the transaction.

Finally, dispute resolution is very complex if a business transaction is involved (or alleged). It will be simpler for all parties if this unhelpful distinction is removed and all EFT disputes are resolved according to the same rules and procedures.

6. EFT Code, Part A (Requirements)

Q12 – Should the requirement in cl 3.1 to provide written notification in advance of an increase in a fee or charge be replaced by another process? For example, should the notice appear in the national or local media on the day on which the increase starts?

There is no evidence that national media notices are an effective form of disclosure. Newspaper circulation in Australia is not keeping pace with population growth and English-language newspapers do not reach a large proportion of the population. Financial institutions are unlikely to use broadcast media to provide notice of increased bank fees, especially as their argument against the current notice requirement is essentially based on costs.

In practice, EFT Code notices are supplied as part of existing communication with customers (e.g. bank statements) and do not represent an additional burden on institutions.

Q13 – Should cl 4.1(a) be revised to allow users to ‘opt-in’ to receive a receipt?

Consumers are likely to accept that this is an area where the EFT Code can be made more flexible to reflect the practical realities facing financial institutions across a growing number of delivery channels. The opt-in model proposed in the consultation paper appears suitable.

Q14 – Should cl 4.1(a) be revised to deal with the problem of ATMs or other machines running out of paper for receipts? If so, how should it be amended?

Consumers are likely to accept that this is an area where the EFT Code can be made more flexible to reflect the current practices of ATM operators. The revision of Clause 4.1(a) proposed in the consultation paper appears suitable.

Q15 – Should cl 4.1(b)(v) be changed to allow a receipt for an EFT transaction by voice communication to specify the merchant identification number instead of the name of the merchant to whom the payment was made?

Consumers are likely to accept that this is an area where the EFT Code can be made more flexible to reflect the practical difficulties posed by telephone / voice systems. The revision of Clause 4.1(b)(v) proposed in the consultation paper appears suitable.

Q16 – Should the EFT Code give more guidance on cl 4.1(a)(viii) regarding balance disclosure on receipts? If so, what guidance should be added?

Further guidance on balance disclosures is not a priority. This does not appear to be a significant issue and perhaps resources could be directed at higher priority issues.

Q17 – Is there duplication or inconsistency between Part A of the EFT Code and the requirements of the Corporations Act that should be reviewed? How should any such issues be dealt with?

If the Code was inconsistent with legal requirements this would be cause for concern. However, no significant inconsistencies have been identified. Minor overlaps and duplication between codes and law are common and are not a significant issue. This does not appear to be a significant issue and perhaps resources could be directed at higher priority issues.

Q18 – Are there aspects of the product disclosure regime under the Corporations Act that should be adopted as part of the regulatory framework under Part A of the EFT Code?

It would be inappropriate to extend the Corporations Act approach to risk to include the security risks posed by EFT systems. A significant body of law is emerging to assist in the interpretation of risks that must be disclosed under the Corporations Act. The security risks posed by EFT systems would appear to be in an entirely different category. It may be more efficient to find another mechanism – elsewhere in the EFT Code – to discuss security risks, without raising any potential confusion with the term ‘risk’ under the Corporations Act.

Q19 – Should cl 7 be revised to specifically require subscribing institutions to identify and correct discrepancies between amounts recorded on the user’s electronic equipment or access method as transferred, and amounts recorded by the institution as received? What are your views on the suggested redrafting?

The use of the word ‘deposit’ in this Clause does appear to limit the effectiveness of the Clause. The revision of Clause 7 proposed in the consultation paper appears suitable.

The more substantial issue is whether financial institutions should also be obliged to identify the source of the error and to correct it. Most consumers probably already believe that institutions are obliged to carry out this basic task and the EFT Code should reflect this.

Q20 – Should the EFT Code include a definition of the term ‘complaint’ under cl 10? If so, should it adopt the definition in AS ISO 10002–2006? Does the standard sufficiently address uncertainty about what is a complaint for the purposes of the EFT Code? Are there any other steps that might be taken to assist stakeholders to understand what is meant by a complaint under the Code?

Consumer stakeholders support the broadening of the definition of the term ‘complaint’. The parties to this submission have read and endorse the recommendations on this issue contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Q21 – Should AS ISO 10002—2006 become the required standard for internal complaint handling under the EFT Code?

The parties to this submission have read and endorse the recommendations on this issue contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Q22 – Should account institutions be given a brief period within which to investigate a complaint before they must give the complainant written advice on how they investigate and handle complaints (as required under cl 10.3)? If so, what is an appropriate period?

Consumer stakeholders prefer complaint information to be provided immediately. If a brief period is to be allowed for internal consideration it should be restricted to a maximum of one day. The parties to this submission have read and endorse the recommendations on this issue contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Q23 – Should any changes be made to the timeframe for resolving complaints under cl 10 of the EFT Code?

Consumer stakeholders would like to see financial hardship taken into consideration in the application of complaints timeframes. The parties to this submission have read and endorse the recommendations on this issue contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Q24 – Do you have information or views about the level of compliance with cl 10?

Although no additional quantitative data is available, consumer stakeholders are concerned that case studies indicate problems with compliance. The parties to this submission have read and endorse the recommendations on this issue contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Q25 – Has the procedure in cl 10.12 been an effective incentive to compliance? Are further incentives required, and if so what form should they take?

There is no evidence that Clause 10.12 has been used. The parties to this submission have read and endorse the recommendations on this issue contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Q26 – Should the EFT Code be amended to cover situations when the subscribing institution is unable to, or fails to, give the dispute resolution body a copy of the record within a certain time? If yes, should the Code specify that a dispute resolution body is entitled to resolve a factual issue to which a record relates on the basis of the evidence available to it?

Case studies have revealed some significant issues with record keeping by financial institutions. The parties to this submission have read and endorse the recommendations on this issue contained in the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

Q27 – Should there be a time after which EFT Code subscribers are no longer required to resolve complaints about EFT transactions on the basis set out in Part A of the Code?

Consumer stakeholders accept that some limitation period should apply. However, it is important that the period only begins when the consumer becomes aware of the breach, and that financial institutions do not unfairly rely on limitation periods to discourage legitimate complaints. For further details please refer to the Consumer Caseworker Submission.

7. EFT Code, Part A (Liability)

Q28 – Should account holders be exposed to any additional liability under cl 5 for unauthorised transaction losses resulting from malicious software attacks on their electronic equipment if their equipment does not meet minimum security requirements? Do the benefits and costs of extending account holder liability justify such an extension of cl 5? What implementation issues would have to be addressed?

This is a vital issue to be addressed in the Review. Consumers will be seriously disadvantaged if they are required to accept any additional liability resulting from malicious software attacks and/or failure to adequately secure their computer.

Some financial institutions appear to support (either through submissions to the Review or in terms and conditions) an increase in consumer liability where there is malicious software on their computer. In the absence of clear direction from the EFT Code, terms and conditions are likely to be extremely harsh for consumers. For example, one bank (Westpac) has already included a Spyware Clause in their terms and conditions:

If you knowingly use a computer that contains software, such as Spyware, that has the ability to compromise access codes and/or customer information, you will be infringing our rules for access code security referred to above and we will not be liable for any losses that you may suffer as a result [emphasis added].

Enforcing such a Clause would be difficult, but its presence may be a deterrent to a consumer with a legitimate EFT complaint, if for example they believe their complaint may result in an intrusive investigation into the contents of their personal computer.

It is also difficult to envisage circumstances in which account holders have displayed such a degree of carelessness in ensuring their computer meets minimum security requirements that liability should be imposed upon them for any resultant financial loss from a malicious software attack.

In addition, the task of defining acceptable ‘minimum security requirements’ is problematic due to a number of practical issues:

- Internet malware is a moving target. Security risks and technical attack vectors change. It is unreasonable to expect that end-users are aware of these risks and attacks, or that they are capable of monitoring and responding to changes. Financial institutions on the other hand have specialised security resources and processes that are dedicated to addressing these risks.

- Consumers access online financial services from a wide variety of computing platforms. These range from mobile devices and the latest desktop operating systems through to legacy systems such as Windows 98. Legacy platforms typically do not support many of the security software tools that provide some protection against the current generation of malware. It may be unreasonable to exclude customers with legacy platforms from access to online financial services. The cost of software and hardware upgrades to an acceptable platform will be prohibitive to some end-users.

- The number and variety of end-user security tools is constantly changing. These tools include browser chrome security enhancements, email filtering software, software-based firewalls, virus scanners and spyware detectors. Software vendors are required to release new versions to address new security threats and to meet their business objectives. It is unrealistic to expect that all end-users will be able to identify the correct combination of tools and versions that must be installed. Moreover, software tools that attempt to combat malware are usually unable to detect the very latest forms since the updates to such software typically lag behind the development of new forms of malware.

- The cost of installing, configuring and maintaining an effective security defence will be prohibitive for some consumers.

- The effectiveness and reliability of end-user security tools is highly variable. Many of these end-user technologies rely on heuristic methods to (either directly or indirectly) detect or avoid malicious software and phishing attacks rather than more dependable techniques.[25] The effectiveness of particular software against malicious software attacks may also be affected by other variables including the operating system used and the specifications of the user’s machine. It is unreasonable to expect that, in these circumstances, end-users will be able to evaluate the effectiveness of these tools. These consumer-grade tools are generally inferior to the levels of protection offered by technologies installed at the financial institution end to prevent these attacks affecting an account-holder in the first place. For example, the State of Spyware (Q2 2006) Report stated:[26]

Overall spyware infection rates continue to rise for the third straight quarter. The second quarter of 2006 saw an increase in the share of consumer PCs infected with spyware: from 87 percent in Q1 2006 to 89 percent. This increase in spyware infections suggests that although home computer users are adopting anti-spyware programs, they are choosing inadequate programs to protect their computers or not keeping their programs up-to-date. Before installing an anti-spyware program, home computer users should evaluate the program’s ability to detect and remove all types of spyware, especially malicious programs.

- Account holders, even if they have some computer experience, will often have difficulty interpreting messages that the software may display to them regarding the probability they are being subjected to a malicious software attack.

- Microsoft Windows is the predominant end-user platform. Windows is the target of the overwhelming majority of malware released in the wild. This malware continues to exploit critical security flaws. In some cases security fixes are released weeks or months after the vulnerability is found. End-users may conscientiously patch their operating system, but they are dependent on Microsoft to release timely patches.

- The effectiveness of software that needs to be installed by account holders on their own machines is dependent on their computing knowledge and motivation to ensure that the software is successfully installed and continually updated. Clearly computing knowledge and motivation would vary amongst account holders. For example, users who only access online banking services on a monthly basis may be less inclined to ensure relevant software is updated regularly than users who access their accounts online on a daily basis.

- Installing software at the user-end would prove particularly impractical in situations where users need to access Internet banking services from public machines or networks (for example, in Internet cafes). It is naive to expect that these machines and networks are protected against malicious software attacks. Financial institutions have promoted the flexibility of Internet banking and the entire system relies on consumers being able to access their accounts from public Internet facilities such as libraries and Internet cafes.

- It is unreasonable to expect that security tools will be installed correctly and optimised to meet the specific threats that affect the financial services industry.

- It may be prohibitively expensive for the financial services industry to maintain an agreed list of technologies, configurations and threats that comprise the ‘minimum security requirement’. It will also be very difficult to effectively communicate that list to consumers, especially if it changes regularly.

Given these considerations, the task of defining what constitutes ‘minimum security requirements’ for the purpose of determining when account holders are liable for financial loss flowing from malicious software attacks is particularly difficult.

It would appear more practical and economically efficient for measures to be implemented at the financial institution end since the protection afforded would then diffuse from a central point to the entire base of consumers utilising Internet banking services. Moreover, many of the developments in security in recent years would not have occurred if the security effort was more diffuse – i.e. in the hands of consumers rather than financial institutions.

Q29 – Should an additional example be included in cl 5.6(e) specifically referring to the situation when an account user acts with extreme carelessness in responding to a deceptive phishing attack?

It may be that there are certain situations in which account users have acted with a degree of carelessness to a phishing attack that is considered ‘extreme’ such that liability should be imposed upon them for any resultant financial loss. However, the notion of ‘carelessness’ should be carefully demarcated with respect to phishing attacks for a number of reasons:

- Firstly, it is important to remember that, although there is a range of authentication technologies available to end-users to assist with detecting phishing attacks, these are generally less effective than technologies that can be implemented by financial institutions.[27]

- Secondly, financial institutions have been instrumental for some time in promoting the use of the online channel to their customers. Despite having the option of encouraging, or even compelling, customers to shift to the use of other channels for banking so as to avoid the problem of phishing attacks (including telephone or face-to-face banking), they have avoided doing so. In this regard it must be remembered that financial institutions reap significant benefit in the form of cost savings by encouraging their customers to perform banking transactions online.

- Thirdly, if the financial services community does not know why consumers repeatedly respond to phishing attacks, then it is pointless and unfair to impose liability on them for responding more than once. If consumers genuinely think that they are taking appropriate action, and genuinely think they are responding to a message from their institution, then making them liable in those circumstances would just seem to have the effect of discouraging them from using Internet banking. Further research on why consumers respond to attacks would help design appropriate security defences, rather than simply shifting liability to consumers.

For these reasons, employing a broad definition of ‘carelessness’ in Clause 5.6(e) in order to impose a greater degree of liability on bank customers in relation to losses flowing from phishing attacks is unwarranted.

Q30 – Apart from this possible clarification, should account holders be exposed to any additional liability under cl 5 for unauthorised transaction losses because of a deception-based phishing attack? Do the benefits and costs of extending account holder liability justify such an extension? What implementation issues would have to be addressed?

The current liability regime for unauthorised transactions should not be modified so as to expand the situations in which account holders will be liable for financial losses flowing from phishing attacks. Although there are measures that can be taken by banking customers in order to combat phishing attacks, for reasons that will be discussed below these are considerably less effective than the technologies that can be utilised by financial institutions to deal with phishing. Hence, it is financial institutions who should bear the primary responsibility for implementing solutions to combat forms of online fraud including deception-based phishing attacks.

Potential Responses to Phishing Attacks and other forms of Online Fraud

There are a host of potential solutions that are available to financial institutions to combat phishing and other attacks their customers may be subjected to online. These include:

- 1. Two Factor Authentication Solutions; and

- 2. Website Authentication Solutions which can be installed at either the server (financial institution) or client end.

Each of these types of solutions is discussed below.

Two Factor Authentication Solutions

Two-Factor authentication refers to the use of a dual-layered approach in order to verify the identity of an end-user to a server. For example, an end-user may be required to supplement a password they have memorised (something they know) with something they have (such as a hardware token that produces a random sequence of digits at pre-determined intervals) or something they are (such as a fingerprint or other biometric data). Examples of two-factor authentication technology include RSA’s SecurID hardware tokens[28] and Australia Post’s joint undertaking with Verisign to produce a two-factor authentication system known as VIP.[29] Both of these technologies involve the use of hardware tokens provided to customers that generate random passcodes at specified intervals of time, which can be used by the customer when logging into the Internet banking section of a financial institution’s website. An alternative system adopted by some financial institutions involves sending random passcodes via SMS to an account holder’s mobile phone when they attempt to log in and/or initiate a transaction.

Two-factor authentication generally represents the limits of what financial institutions in Australia are currently implementing in response to online fraud such as phishing attacks. However, the technology provides only marginally improved resistance against phishing attacks.[30]

There is, for example, a significant possibility that the passcode displayed to a bank’s customer by their hardware token can be intercepted through the use of a spoofed website designed to falsely appear to belong to the customer’s financial institution. The website, if a convincing spoof, could cause the customer to provide the passcode displayed on their hardware token. The fraudulent party who created the spoofed website could then immediately use the passcode to login to the customer’s account as part of a replay attack (assuming they also know the customer’s password and username details). An example of this has occurred recently when account holders with Dutch bank ABN Amro had money stolen from their accounts by fraudulent parties using this very method to circumvent the bank’s use of two-factor authentication.[31]

Hence, there is a need for financial institutions to consider deploying some form of website authentication technology to prevent the use of spoofed websites (typically used as part of a phishing attack) undermining the security of customer’s login credentials.[32] A variety of these technologies are considered below.

Website Authentication Solutions

It is important to distinguish website authentication from two-factor authentication. While two-factor authentication techniques are typically not concerned with authenticating websites to users, website authentication technologies have been specifically developed to enable Internet users to verify whether the actual identity of a website aligns with the represented identity of the website. Website authentication technologies can be installed at either the client (customer) end or server (financial institution) end.

- Server-end website authentication solutions

Although several of the authentication technologies outlined in this section do require some level of user involvement, they have been listed as server-end since they are predominantly dependent on the financial institution for their effectiveness.- Shared Secrets

A technique that is commonly put forward as a means of achieving authentication of a web server is the sharing of a secret between the server and end-user. The user may, for example, provide the server with a personal image that can then be displayed back to them whenever they wish to access the relevant website. If the wrong image is presented, the user will know that they are interacting with a spoofed website. - Keypad Technology

Keypad technology involves presenting an end-user with an mage of a keypad containing a set of symbols that enables them to communicate their password to a web server. One advantage of this technology is that it is not susceptible to keystroke logging malware that may have been covertly installed on a customer’s computer by a fraudulent third party in order to capture passwords the user enters via their keyboard. Keypad technology can also be adapted to authenticate the websites of financial institutions to customers. This makes it even more effective at dealing with phishing attacks. An example of this is provided by Tricerion’s Strong Mutual Authentication keypad technology.[33] - Secure Remote Password (SRP) Protocol

The Secure Remote Password (SRP) protocol prevents a shared secret, such as a password, from being compromised during communications between a financial institution and one of its customers by removing the need for the secret to be sent over a network at all.[34] - Challenge/Response Mechanisms

In the context of website authentication, challenge / response mechanisms involve a client presenting a server with a challenge in order to verify the identity of the server. Using a secret previously shared between the client and server, the server calculates a response and presents it to the client. The client is able to use the response to authenticate the server.[35] - Delayed Password Disclosure (DPD)

An extension of Secure Remote Password protocol, DPD enhances the effectiveness of SRP as a website authentication technology by stipulating the association of numerous images with a customer’s internet banking password. The images are presented sequentially to a customer by the financial institution’s server as they enter each character of their password during a login attempt. This process enables the customer to detect when they are dealing with a party other than the financial institution.[36]

- Shared Secrets

- Client-end website authentication solutions

These technologies are typically installed on the end-user (customer) machine and attempt to detect phishing attacks typically through the use of heuristic analysis techniques. Examples of such solutions include:- Browser Chrome Enhancements

There is an emerging trend in attempting to achieve website authentication by adding to the visual cues presented to users in the area surrounding a typical browser window. This area is commonly referred to as the ‘browser chrome’ and a host of plug-ins can be added to the web browser chrome to assist in the process of detecting spoofed websites, one of the key elements used in a phishing attack. Examples of actual and proposed browser-chrome enhancements include Petname,[37] SpoofGuard.[38] Proposed browser-chrome enhancements include Trusted Password Windows and Dynamic Security Skins.[39] - Email Detection

These technologies use either heuristic or collaborative methodologies to analyse emails received by an end-user and determine whether they are likely to be phishing emails. An example of this is provided by the Cloudmark Network Feedback System.[40]

- Browser Chrome Enhancements

General weaknesses of client-end website authentication solutions

Although, given the inadequacies of two-factor authentication, some form of website authentication is undoubtedly needed for Internet banking in order to more effectively neutralise the threat of phishing attacks, client-end solutions are a less attractive option compared with server-end solutions. One of the reasons for this is that client-end technologies such as those outlined above rely on probabilistic methodologies (such as collaboration and heuristic analysis) in order to detect phishing attacks. This is an inherently less robust fashion of detecting phishing attacks compared to many of the methodologies employed by server-end technologies.

For example, with regard to browser-chrome enhancements the W3C paper on Limits to Anti-Phishing[41] notes:

Adding more trust indicators or more obvious trust indicators (to a web browser user interface) misses the point that an attacker can spoof every part of a user interface, including browser chrome and copy new trust indicators. Some proposals include new UI elements such as new anti-phishing trust icons, company logos in browser chrome, or new authentication popup windows. All of these miss the point that an attacker is capable of spoofing the entire user interface.

The Financial Services Technology Consortium (FSTC) is conducting a Better Mutual Authentication Project. Their recent publication – Financial Industry Recommendations and Requirements for Better Mutual Authentication[42] suggests that although modern web browsers have a fairly sophisticated array of security features, those features (particular those that can be used to authenticate websites) are often poorly integrated into the user interface, with security indicators, alerts and dialogue boxes being difficult to understand. Many end-users have difficulty understanding what the browser is telling them, while users are often provided with the option to make security warnings go away permanently.

Moreover, current web browsers allow websites to easily modify the ‘browser chrome’ – for example, by re-arranging, altering or even concealing certain elements within the browser window. This allows fraudulent parties to mislead users about the site they are viewing.

An additional problem of using browser chrome enhancements to achieve website authentication is evident when one considers that there may be situations in which end-users need to access the same websites from different machines, depending on their location. This means that they will need to install the enhancements on each machine, requiring a degree of effort which many users may simply refuse to invest.[43] Alternatively, different users may elect to install different browser chrome enhancements, each with their own level of effectiveness. Therefore different users accessing the same website may receive differing levels of protection against phenomena such as spoofed websites.

Q31 – To what extent has the restriction on using a user’s name or birth date under cl 5.6(d), been relied on?

It does not appear that any data is available on the self selection of name or birth date as user codes. Prior to the last review of the EFT Code there were some incidents where financial institutions used birth dates as the default telephone access code. This practice no longer occurs.

Some anecdotal evidence is available on current practices:

- Self selection screens for changing access codes tend to carry suitable warning messages about the selection of weak access codes.

- A limited number of self selection processes will automatically reject weak access codes (eg sequential numbers), but these are not (yet) designed to reject name or date of birth.

- Clause 5.6 (d) has not been relied on in practice to the extent that it has come to the attention of consumer stakeholders.

- Criminal activity based on ‘guessing’ common passwords is likely to represent a smaller proportion of criminal activity now that most attacks rely on social engineering or deception to entice the consumer to reveal their password.

Overall, the usefulness of Clause 5.6 (d) is questionable. It never had the support of consumer stakeholders and this Clause is a candidate for removal in the interests of simplifying and shortening the Code.

Q32 – Should the restriction on users acting ‘with extreme carelessness in failing to protect the security of all the codes’ under cl 5.6(e) be further elaborated or extended in some way? Should additional examples of extreme carelessness be given?

The term ‘extreme carelessness’ was considered necessary in the last Code Review because the drafters could not possibly anticipate all of the potential attacks and vulnerabilities in relation to access codes. It is a useful catch-all term that allows other parts of the Code to remain technology neutral. The Clause has overall merit and should be retained.

Reliance on this Clause is limited in practice.

The addition of examples, however, is more problematic. Typically, the example scenarios need to be debated amongst stakeholders to ensure there is common agreement about when liability might shift due to extreme carelessness. Great care is required in the drafting of such examples.

A suggested approach to improving Clause 5.6 (e) is:

- Retain the ‘extreme carelessness’ term in Clause 5.6 (e);

- Consider extending the scope of the Clause to include protecting the security of devices in line with the proposed Technology Neutrality Review; and

- Remove or limit the examples provided to scenarios which have clear agreement amongst stakeholders (this is a task for the Working Group).

Q33 – Should the EFT Code specifically address the situation when an unauthorised transaction occurs after a user inadvertently leaves their card in an ATM machine?

There do not appear to be any advantages in codifying this approach. Perhaps, in the interests of simplifying and shortening the Code, this could be provided as an example scenario in notes rather than including it as a specific Clause in the Code.

Q34 – To what extent is unreasonable delay in notification of security breaches by account users currently an issue? Please provide on the frequency and cost of such delays, if possible. (You may wish to provide this information on a confidential basis.)