Research

Research

Paper - Distributed Identity - Case Studies - Part 1 (September 2003)

- Overview

- Introduction

- Federated identity case study -- Liberty Alliance

- Brokered identity case study - Reach

![[ Galexia Dots ]](/images/hr.gif)

| |||||||||

This paper is the first part in a series of case studies from Galexia on distributed identity.[1]

Part Two[2] of this series looks at the framework of standards being developed by MS and IBM for secure web services interoperability, especially the WS-Federation specification that competes with the Liberty Alliance project and the anticipated WS-Privacy specification.

Overview

Distributed identity schemes are identification and authentication systems which may operate as alternatives to centralised national identification schemes. They include the concepts of federated identity and identity broking.

Distributed identity is being considered as a privacy positive alternative to national identification schemes. This paper argues that while distributed identity may be a reasonable alternative to national identification schemes, distributed identity is not necessarily a privacy positive initiative in its own right. The level of privacy intrusion depends on numerous technical factors and the effective management of privacy issues during design, implementation and the active life of distributed identity systems.

These two case studies accompany a paper presented at the Baker & McKenzie Cyberspace Law and Policy Centre’s Surveillance and Privacy 2003 conference (Sydney, 8-9 September 2003) by Chris Connolly.[3] That paper, The privacy risks and rewards of distributed identity, discussed distributed identity management systems and proposed a set of privacy tools which can be used to assess and manage privacy risks in such systems.

Galexia continues to conduct research on distributed identity systems. These case studies and the accompanying power point presentation provide a brief introduction to the field.

This paper is available in the following formats from <http://www.galexia.com/>:

Introduction

Distributed identity schemes are identification and authentication systems which may operate as alternatives to centralised national identification schemes. They include the concepts of federated identity and brokered identity.

Distributed identity is being considered as a privacy positive alternative to national identification schemes, such as the failed Australia Card proposal[4] and the failed proposal to merge Government databases in Ontario, Canada.[5]

Although distributed identity may be a reasonable alternative to centralised national identification schemes, distributed identity is not necessarily a privacy positive initiative in its own right. The level of privacy intrusion depends on numerous technical factors and the effective management of privacy issues during design, implementation and the active life of distributed identity systems.

This paper provides a brief overview of current issues in distributed identity, and two detailed case studies.

Defining distributed identity

Distributed identity involves the exchange of identity information across one or more trusted domains (either within a single organisation or between different organisations) in such a way that the information is maintained at its original source.[6]

To manage authentication and verification, distributed identity systems may utilise either:

- a ‘web of trust’ (federated identity), or

- a ‘trusted third party’ (brokered identity).

Where it is necessary for users to gain access to multiple applications provided by multiple organisations, distributed identity allows single sign-on by passing through user authentication and authorisation credentials.

In a recent document by Hewlett-Packard looking at federated network systems, such a network is described as:

‘A networked world in which individuals and businesses can more easily interact with one another, while respecting the privacy and security of shared identity information.’[7]

Often, a common feature of distributed identity systems is that users are provided with an opportunity to exercise some control over the type and amount of information disclosed to different organisations for different applications.

Trends and drivers in identity management

The need for identity management systems, including distributed identity solutions, is being driven by several trends. The motivation for the wider acceptance and use of these systems comes from a variety of sources within both the public and the private sector.

Government trends

The uptake of eGovernment will involve, as a key prerequisite, the coordination and facilitation of the development of a trusted and secure online environment for delivery of government services, to both individuals and businesses. However, government agencies appear to remain uncertain of the availability, cost-effectiveness and inter-operability of technologies, tools and standards for identifying and authenticating online customers. Consequently, this is holding back the rollout of more complex or sensitive eGovernment services and transactions, thereby delaying more widespread benefits of eGovernment.

‘Electronic authentication is qualitatively different for the public versus the private sector because of government’s unique relationship with citizens:

a. Many of the transactions are mandatory;

b. Agencies cannot choose to serve only selected market segments;

c. Relationships between government and citizens are sometimes ‘cradle to grave’, but characterised by intermittent contacts, which creates challenges for technical authentication solutions; and

d. Individuals may have higher expectations for government agencies than for other organisations with regard to protecting the security and privacy of personal data.’[8]

In Australia, Commonwealth government agencies are working with the National Office for the Information Economy (NOIE) to develop an identification and authentication framework which can accommodate various agencies’ business processes while providing common standards and rules.[9]

There is also a strong international interest in eGovernment initiatives.[10]

Business trends

Businesses are investigating the use of identity management systems to provide services more efficiently. Costs can be reduced by sharing authentication and verification credentials across a wider range of organisations - rather than creating standalone authentication systems for each organisation and/or application. Identity management systems may enable multiple-subsidiary e-business transactions to be streamlined and simplified.

Key issues in identity management

Identity management systems do not exist in a policy vacuum. The context and setting for identity management solutions have a direct impact on design and implementation.

All identity management solutions, whether centralised or distributed, need to address the following key issues.

Addressing these key issues at the design stage of identity management systems has significant benefits over attempting to manage these issues post-implementation. Management of these issues in distributed identity models is essential, and it should not be assumed that distributed identity models will ‘automatically’ be more effective at addressing these issues than centralised identity models.

Models for eAuthentication

The strength of the authentication method employed in any system should be commensurate with the value of the resources (information or material) being protected.[11]

Evidence of Identity (EOI)

Sufficient levels of trust and confidence must be generated in the accuracy and validity of information which is presented as original evidence of identity.

‘Many of the foundational identification documents used to establish individual user identity are very poor from a security perspective, often as a result of being generated by a diverse set of issuers that may also lack an ongoing interest in ensuring the document’s validity and reliability.’[12]

Data retention

Sufficient records must be retained to assist in future investigations or inquiries. The validity and accuracy of such records must be balanced against privacy interests.

Privacy

Appropriate privacy controls must be provided within the solution, including the ability to provide anonymity where necessary. Privacy controls need to go beyond simple compliance with national and international privacy laws. They also need to meet the privacy expectations of consumers.

Identity fraud and identity theft

Identity management systems need to limit opportunities for common identity fraud (one off fraud which usually relies on the adoption of another person’s identity for a single transaction) and provide adequate prevention against identity theft (more sophisticated fraud where a false identity is assumed for the purposes of opening accounts, obtaining multiple goods and services etc.).

Legal liability

Identity and authentication system users also wish to ensure that they are properly protected by the law. The allocation of legal liability for unauthorised transactions must be determined for each solution.

Federated identity case study -- Liberty Alliance

Overview

Liberty Alliance is an example of a federated identity solution - a type of distributed identity which relies on communities of trust.

Other federated identity models include WS-Federation,[13] Microsoft .NET Passport and smaller, sectoral initiatives.

Liberty Alliance[14] is an open technical specification for sharing personal information through computer networks like the Internet. It is highly sophisticated and mainly useful to very large corporations and government organisations that conduct transactions online.

It employs the concept of federated identity, where (the concept supposes) personal information remains in the hands of the original collector and is shared across a wide range of providers, instead of consolidated into a master database. The relationships between providers are regulated by private contract, and, of course, applicable privacy and data protection laws.

Liberty incorporates a number of thoughtful and effective measures with regard to technical aspects of privacy, such as anonymous cross-site authentication. However, it rightly asserts that it cannot enforce many policy aspects of privacy on its users.

History

A way of uniformly identifying users across the Internet has haunted the dreams of marketing directors and the nightmares of privacy advocates. However, for a long time the financial costs of such a system were prohibitive, given the marginal benefits.

Unsurprisingly, Microsoft, ever the long-term investor and innovator, was the first company to make a foray into such an identity system. Code-named ‘Hailstorm’ - already a fatal mistake - it proposed a vast Microsoft-controlled database where the user registered all their details once and could then browse the web seamlessly.

It was the momentum of both consumer and corporate opposition to the Hailstorm concept that gave birth to the ‘Liberty Alliance’ in September 2001 - a consortium of major companies spearheaded by Microsoft competitor Sun Microsystems. The group explicitly aimed to provide an alternative and more privacy-friendly system by creating a specification for managing a ‘federated network identity’.

Phase 1 of the Liberty Specification was released in July 2002, revised to version 1.1 in January 2003. It only dealt with the basic cross-site authentication feature of the system, allowing users to navigate among different sites without signing in to each with a password, and did not describe any system for exchanging personal information.

The Phase 2 draft was released in April 2003 and a revision in August 2003, outlining more significant Liberty features - the permission-based sharing of information. The final release of Phase 2 was published in November 2003.

Technical outline

The Liberty standard is in fact a series of standards and specifications. The current working document is the Liberty Alliance Phase 2 Final Specifications.[15] Key aspects of the specifications are set out below.

Liberty Identity Federation Framework (ID-FF)

The Liberty Identity Federation Framework is the foundation of the Liberty Alliance protocol and provides functionality such as opt-in account linking and single sign-on capabilities. The Phase 2 revision of the ID-FF also incorporated:

- Affiliation

This enables a user to choose to federate with a group of affiliated sites, a critical need for portals and business-to-employee applications; and - Anonymity

This enables a service to request certain user attributes without needing to know the user’s identity.[16]

Liberty Identity Web Services Framework (ID-WSF)

The Liberty Identity Web Services Framework outlines the technical components necessary to build interoperable identity-based web services. Specific features include:

- Permissions-Based Attribute Sharing

This allows an organisation to offer users individualised services based on attributes and preferences that the user has chosen to share; - Identity Discovery Service

This allows a service provider to dynamically discover the location of a user’s identity services, and for the identity provider to respond based on the user’s permissions. This feature is critical for being able to offer a large number of users real-time identity-based services; - Interaction Service

This allows an identity service to obtain permission from a user (or someone who owns a resource on behalf of that user) to allow them to share data with the requesting service; - Security Profiles

This describes the profiles and requirements necessary to protect security and ensure the integrity and confidentiality of messages; and - Extended Client Support

This enables hosting of Liberty-enabled identity-based services on devices without requiring HTTP servers. This is useful since most consumers do not run HTTP-servers on their PCs, and many networks do not support running HTTP-servers on consumer devices. This also reduces implementation costs in resource-constrained devices such as mobile phones.

Liberty Identity Service Interface Specifications (ID-SIS)

In Phase 2 and future phases of its specifications, the Liberty Alliance will be developing a collection of new specifications that offer companies a standard way to build interoperable identity-based services - the Liberty Identity Service Interface Specifications (ID-SIS). So far, these services include:

- ID-SIS-Personal Profile

This service defines a template for basic profile information, typically used in registration. It includes a standard set of attribute fields (name, legal identity, legal domicile, work address, email address) so organisations have a common language to speak to each other and offer interoperable services. - ID-SIS-Employee Profile

This service defines a template for employee information, which, in additional to regular personal details, holds employment related information such as position and company history.

Technical privacy features

Liberty Alliance was founded as the pro-privacy alternative to MS Passport, and despite the fact it is being developed and funded by markedly privacy-unfriendly types of organisations like credit card companies, telecoms and banks, it has devoted considerable effort to incorporating privacy protections into the specifications. Such features include:

- Digital signing of all Liberty messages using XMLDsig, which provides authentication, confidentiality, message integrity and non-repudiation. This means privacy-managed transactions can be audited with certainty;

- Anonymous and pseudonymous access capabilities;

- UsageDirective tags, which provide significant low-level privacy transaction management features of the Liberty protocol:

- A requestor can indicate the intended use of data to the provider;

- A provider can direct a requestor what it can use the data for;

- Alternatively, a provider can reply to a requestor with a UsageDirective that expresses acceptable practices before providing any data.

- The consent header tag, which is used to claim that a data subject has consented to a particular transaction;

- The Interaction Service specification, which enables service providers to contact a user directly to obtain consent or additional data for a particular transaction

The challenges for Liberty Alliance

The challenge for online authentication systems is that they have not yet reached the stage where they offer practical benefits and applications to consumers. A 2002 Gartner report[17] found that people are generally distrustful of, and uninterested in, broad online authentication systems. Liberty members seem to hope that consumers will be attracted to federated identity because of problems with existing authentication systems:

‘Fast-forward to the grown up and modern world. Pieces of their [consumers] identity are now scattered across an endless list of entities; banks, credit card companies, brokerage firms, insurance companies, national IDs, pension funds, medical providers, and the places where they work. The Internet has become one of the prime vehicles for business, community and personal interactions, and it is fragmenting this identity even further. Pieces of their identity are doled out across the many computer systems and networks used by employers, Internet Service Providers, bulletin boards, instant messaging applications, and online commerce and content providers. This all occurs with little coordination, interaction, or control on their part.

The result is a fairly high level of frustration for everyone involved. People have to repeatedly enter the same information within the workplace and in personal business dealings. The IT manager must provision dynamically changing accounts to reflect up-to-date roles and identities within the organization. The sales executive needs to reach the audience with the right identities to sell a product.’[18]

Despite the picture painted by this passage from a Liberty document,[19] the broad usage of Liberty in retail e-commerce seems some time away. Given consumer resistance and the expense of deployment, it may be some time before Liberty becomes a pervasive standard on the Internet.

The more viable - and less privacy intrusive - applications are for more discrete networks of users and providers, rather than large scale business-to-consumer applications. For example:

- Financial trading communities

A relatively small set of users who would benefit from consistent access to a variety of disparate market systems. The privacy implications are limited given that only limited personal information is needed, and the usability benefits are significant; - Student and employee intranets

Large companies, universities and other education institutions often have a number of separate internal IT systems. Here the incentives for identity fraud, or privacy abuse by the controller, are low, and the benefits once again are significant. (In Australia, however, it is important to note the legal vacuum relating to employee privacy); and - eGovernment

Although the risks of identity fraud are significant, governments are generally subject to a degree of privacy regulation and oversight, and the efficiency and cost savings from achieving interoperability between various government applications provide a genuine incentive to governments to be some of the first adopters of Liberty technology.

However it is large consumer corporations - credit card companies, technology vendors and private telecommunications providers, who are currently considering the future benefits of Liberty, and backing the Liberty Alliance:

‘Deploying [single sign-on] functionality will drive additional requirements for attribute sharing in order for banks, insurance companies, brokers or others in the industry to deliver more personalized services to their users. Liberty’s first set of specifications and future work is playing an important role in this area.’[20]

This vision of seamless web services for consumers is not so comforting to privacy advocates. Despite the protests to the contrary by Liberty Alliance backers, the fact is that wide deployments of any particular standard in online authentication and information sharing can raise potential privacy risks:

- Identity theft

By allowing a single authentication at, for example, a superannuation website to give a user access to insurance, banking and trading services, single sign-on systems increase both the vulnerability and incentive to identity thieves. The risk increases as the system spreads across broader e-commerce sectors; and - Targeted marketing

As can be seen in the passage above, Liberty supporters openly anticipate trading in personal information with each other to profile their consumers.

Given that Liberty is a draft technical standard, and does not have any enforceable control over implementations, consumers will have to rely on existing privacy regulatory schemes and trust corporations to run their Liberty-enabled systems responsibly.

The future for Liberty Alliance

From a privacy perspective, Liberty Alliance is a vast improvement on the original Microsoft Passport concept of a centralised database. However, as discussed in Part Two of Galexia’s papers on distributed identity, Liberty’s main competitor is now the WS-Federation specification of the web services suite being created by Microsoft and IBM.

Liberty has some significant advantages. The business-related aspects of the Liberty project are far more advanced than WS-Federation, reflecting the fact that Liberty is a business-led effort. However, Liberty has precious little time to establish itself as a working standard for identity federation before the release of the next Windows operating system. Codenamed ‘Longhorn’, it will include WS-Federation as part of its built-in web services protocol suite. There are no technical barriers to the two standards working alongside each other, but Liberty was founded directly against Microsoft and neither seems to have forgotten.

Liberty should recognise that the key to establishing identity federation is persuading consumers, not businesses. It must take some responsibility for providing comprehensive guidelines and promoting good privacy among its members.[21] Its online tools will need to be supported by enforceable customer-protective policies and practices (of the organisations using those tools), for Liberty to be seen as offering a privacy-sensitive identity management solution. The success of Liberty’s concept of ‘federated network identity’ rests on its ability to ensure that information sharing does not run rampant over the interests of consumers.

Brokered identity case study - Reach

Overview

Reach[22] is an example of brokered identity - a form of distributed identity management which relies on the services of a trusted third party to manage authentication and identity on behalf of consumers.

Reach is an agency established by the Irish Government in 1999 to develop a strategy for the integration of public services and to develop and implement a framework for eGovernment. In May 2000 Reach was commissioned by the Irish Government to develop the Public Services Broker (PSB). Since then, Reach has focussed on defining and implementing the architecture and principles underlying the operation of the PSB.[23] Reach’s mission statement is:

‘to radically improve the quality of service to personal and business customers of Government and to develop and deploy the Public Services Broker to help agencies achieve that improvement. In particular Reach is to develop and implement an integrated set of processes, systems and procedures to provide a standard means of access to public services, to be known as the Public Services Broker.’[24]

This electronic broker will act as a helper or assistant between customers and Public Service Agencies. It will be developed by Reach and then subsequently be operated by a separate agency. The PSB is not intended to act as a representative or advocate for government agencies.

As part of its work with the PSB, the Reach project is developing standards and legislation that will deal with issues of interoperability, Internet security and privacy. Reach’s roles and objectives fall into three key areas:

- standards and operational policies;[25]

- co-ordination and leadership;[26] and

- implementation and delivery of infrastructure and systems.[27]

Reach aims to provide a one-stop service for public service customers; enabling them to access related services at a single point of contact and to give their information, and prove their identity, once only, instead of having to go through the same procedure separately for each related service. To improve services in this way, internal business processes need to be integrated. Data-sharing is a key to facilitating the seamless delivery of public services - it promotes customer service and efficiency and reduces the need to call for physical documents.

However, there is also the requirement of meeting customers’ expectations that data is kept securely and that their privacy is respected. In response to this, the Reach model seeks to balance the need for the availability of data to public service agencies while ensuring a high level of privacy and respect for data protection principles.

Reach is implemented as an element of the Irish Government’s broader eGovernment strategy which aims to ensure quality of service to people dealing with government agencies and improvements in administrative efficiencies.[28] Reach is also responsible for ensuring that the development of electronic Government in Ireland is done in the context of European Union initiatives. This involves complying with the eEurope Action Plan[29] which sets the eGovernment strategy in the wider European context and places certain eGovernment development obligations on Ireland.

Description of Reach

Public Service Broker (PSB)

The Public Service Broker (PSB) is the central component of Ireland’s eGovernment strategy. It provides a common access point for eGovernment services, identity management and access control, common interface standards, procedures and supporting services with the necessary infrastructure to make access to eGovernment services as straightforward and secure as possible.[30] The PSB aims to improve delivery of services to the public through traditional means (in person and on the phone) and the new self-service electronic channel.[31]

The Public Services Broker model involves an integrated approach on three levels:

- a single access point to related services (integration across agencies, services and transactions);

- updated data available in real-time and data available for repeat transactions (integration across time); and

- the same data and experience available across the three main access channels - counter, telephone and the Internet (integration across channels).

The Public Services Broker model is based on a hub architecture. Hubs at central, sectoral or local levels are used to exchange data to support common services at the appropriate level and sectoral data stores can be supported by central authentication and security services. This means that data captured once can be reused by other agencies and on other occasions. One element of proposed privacy protection is to enable consumers to know, and exercise control over, how their personal information is used.

The Public Service Broker is not a single application, rather it can be viewed as:

- a portal;

- a user access management system;

- a set of PSB user services;

- a set of PSB management services; and

- an integration framework - a set of components and tools that will be used to integrate the above services and to PSB-enable Government services.

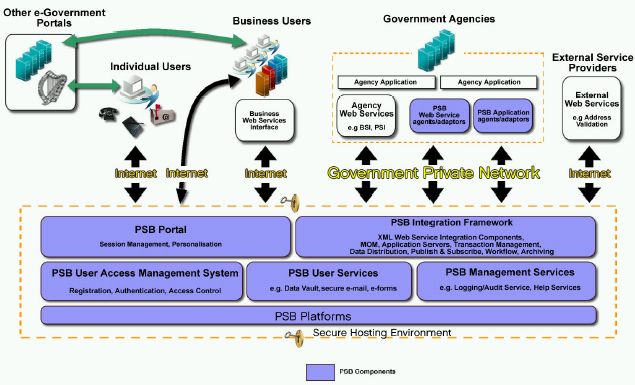

The complexity of the PSB and its role in the provision of eGovernment services is represented in the diagram below:

|

|

High Level Schematic view of PSB architecture[32] |

Terms of reference

Reach’s terms of reference are to:

- Develop the framework for delivering integrated public services to individual customers and businesses in Ireland.

- Develop and implement the framework for electronic delivery of public services - the ‘eGovernment’ and Information Society agendas.

- Co-ordinate the eGovernment programme across the Public Service.[33]

Reach’s mandate is to:

- Develop and implement an integrated set of processes, systems, and procedures to provide a standard means of access to public services, to be known as the Public Services Broker. This will be done in consultation with Public Service delivery agencies and customers.

- Develop the existing Public Services Card as the customer’s secure key to accessing public services.

- Promote the use of the Personal Public Service Number (PPS No.) - formerly the RSI Number - by the public and by authorised Public Service agencies.[34]

Reach’s legal framework

Reach was established by Government decision in 1999 and its mandate extended, again by Government decision in 2000, to develop the Public Services Broker.

Reach grew out of the Integrated Social Services Strategy adopted by the Government in 1996 that recommended the integration of public services, increased sharing of data and the extension of the use of the RSI Number across the public service in the interest of improving customer service.

The legal framework for the sharing and use of essential personal data is set out in a number of Acts, viz. Data Protection Act 1988,[35] Social Welfare Acts 1998,[36] 1999[37] and 2000[38] and Social Welfare (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2002[39] and the Health (Provision of Information) Act 1997.[40]

The Minister for Social, Community and Family Affairs, whose Department is responsible for the issue of Personal Public Service Numbers and the Public Services card, reports to Government on the progress of the Reach initiative.

Reach’s Inter-Agency Messaging Service

Reach developed the Inter-Agency Messaging Service (IAMS) to support the electronic exchange of customer data among agencies in the public service. The IAMS will initially allow the exchange of birth registration data between the General Register Office (GRO) and the Department of Social and Family Affairs’ Client Identity Services Section (CIS), and between the GRO and the Central Statistics Office (CSO). This service will eventually be extended to support the capture and dissemination of death and marriages notification data among a wider range of agencies.[41]

Current status of Reach

As at February 2003 the development and implementation of the PSB and other components of the eGovernment strategy were behind schedule.[42] Reach is continuing to develop and refine requirements and policy documents for its various projects, including the Inter-Agency Messaging Service, and in particular the PSB.

In June 2003 Reach announced that it had selected four suppliers to continue developing the PSB in the procurement process.[43] A final supplier is expected to be announced in November 2003 and will implement the Broker in light of Reach’s technical specifications.[44]

The reachservices website[45] was launched in April 2002 and is intended to be the single gateway to government services online. It is a significant component of Ireland’s centralised model of eGovernment.

Privacy issues in Reach

In terms of privacy protection on a legal level, Reach initiatives are being created within the framework of the Data Protection Act[46] and the Freedom of Information Act.[47] The provisions of the Social Welfare Acts[48] also contain safeguards for the protection of the individual’s right to privacy.[49] Pivotal to the initiative is that users will have control over their personal information - they are given discretion over disclosure of their personal information to government bodies. Furthermore, the Public Service Broker is independent of public service agencies, acting as both an ‘agent for customers and a shop-front for the public service.’[50]

In terms of the practical mechanisms used to protect privacy, the Personal Public Service Number (PPSN) serves as the customer’s unique key which will help the development of personalised services and minimise the risks of error and inaccuracies in personal records. The customer will be able to deposit personal data with the Public Services Broker, and later choose to release it to a public service agency when applying for a service.[51] This does not mean, however that a personal profile is going to be built on every person in the country. Only the minimum data required for a particular transaction would be viewable by the staff member assisting the customer. The Broker would give the individual customer as much control as possible over the release of personal data from their personal data stores. All accesses to personal data will be recorded and staff will be unable to view personal profiles unless the customer grants permission by keying in a PIN or password.[52]

A key issue for Reach (and brokered identity in general) is ensuring that the community has a sufficient level of trust in the identity broker. This trust can be difficult to achieve, especially in communities where the government and private sector have a history of privacy intrusion and privacy abuse. In Ireland, the Reach initiative has attempted to win community trust through adoption of the following measures:

- Legislation

Legislation already exists on the collection and storage of personal information. In addition, the creation and use of PPS Numbers and Public Service Cards is vested by law in the Minister for Social Community and Family Affairs; - Transparency

To ensure people understand how personal data will be kept secure, the rules and procedures for collection and release of personal information will be published; - Oversight

Additionally, compliance with those published procedures and legislation is further subject to scrutiny by a number of statutory holders, namely the Comptroller and Auditor General, the Ombudsman and Information Commissioner and the Data Protection Commissioner; and - Choice

The Public Services Card (a smart card containing the PPSN and other necessary personal identifiers) will not be a national identity card. It is designed to meet the needs of people to identify themselves when using public services. The new card does not have to have a photograph, date of birth or any other personal data. It could, for example, be like an ATM card, which when used with a PIN sufficiently identifies the person to draw down cash from ATM machines or carry out banking instructions. The key principle to be adopted is that customers choose the additional features that can be added to their basic card.[53]

The Reach model aims to give consumers customised options for limiting the use of their data.

Commentary

The Irish government, through Reach, has worked hard to design a privacy friendly brokered identity system. Reach’s underlying philosophy of giving the consumer control over their personal information has enabled them to develop an effective ‘one stop shop’ model of eGovernment that is founded on consumer rather than government control of information.

However, there are some hurdles that Reach are yet to overcome. Firstly, the implementation of the PSB is severely behind schedule; and secondly it appears that the public are yet to overcome privacy fears about the Internet.

The majority of Irish people (56%) feel that ‘if you use the Internet your privacy is threatened’.[54] This could have important ramifications for the PSB and other eGovernment initiatives. Despite Reach’s priority of consumer data control, these efforts could be rendered ineffective if the public cannot be inspired to use the services once they have been developed.[55]

The future for Reach

Once fully implemented the Reach initiative could subject to appropriate privacy protection, alter the way most people interact with and use government services. The one-stop shop model will provide administrative efficiencies for both the public and public service providers.

These benefits may include:

- Connected services will enable customers to access more than one service through a single access point;

- Personalised services that are founded on the individual needs of the customer and his or her preferences;

- Choice and convenience so that customers will be able to choose the time and place which best suits them;

- Reduction in repeat form filling and provision of basic personal data; and

- Simplification of access to services and information by allowing self-service over the Internet.

The Irish Government hopes that the focus on privacy protection in implementing this initiative ensures that these benefits will be achieved with negligible privacy intrusion. Other jurisdictions will be monitoring the Reach and the Public Service Broker (PSB) implementations to assess their effectiveness and possible use in their own development of eGovernment services.

Chris Connolly, Ian Booth, Prashanti Ravindra, Peter van Dijk, Francis Vierboom

Galexia

![[ Galexia Dots ]](/images/hr.gif)

[1] Galexia, Distributed Identity Case Studies - Part 1, September 2003, <http://www.galexia.com/public/research/articles/research_articles-pa02.html>.

[2] Galexia, Distributed Identity Case Studies - Part 2: The Microsoft/IBM Web Services (WS) Security Framework, November 2003, <http://www.galexia.com/public/research/articles/research_articles-pa03.html>.

[3] Chris Connolly is a Director of Galexia, a specialist consulting firm which focuses on electronic commerce, privacy, authentication and identity management. Chris is also a Visiting Fellow in the Law Faculty at the University of New South Wales, where he teaches Electronic Commerce Law and Practice (amongst other courses) in the Masters Program and a Director of the Financial Services Consumer Policy Centre, a research centre affiliated with the UNSW.

[4] Roger Clarke, Just Another Piece of Plastic for your Wallet: The 'Australia Card' Scheme, June 1987 <http://www.anu.edu.au/people/Roger.Clarke/DV/OzCard.html>.

[5] BIS Shrapnel, October 2002, unpublished.

The Provincial Government of Ontario abandoned its plans to implement the multi-application smart card. The initiative that was recognised as the most far-reaching multi-application implementation in the world. It appears to have been abandoned for four principal reasons:

- Lack of internal cooperation and agreement between government departments;

- Powerful public opposition from Canada’s Federal Privacy Commissioner;

- Financial models proved untenable; and

- Poor management and lack of transparency.

[6] This definition has been adapted from Pato, J, and Rouault, J, Identity Management: The Drive to Federation, Hewlett-Packard Development Company, August 2003, <http://devresource.hp.com/drc/technical_white_papers/IdentityMgmt_Federation.pdf>.

[7] Above at p5.

[8] Committee on Authentication Technologies and their Privacy Implications, Who goes there? Authentication through the lens of privacy, , National Research Council of the National Academes, April 2003 (pre-publication version), at Section 6.2.

[9] Refer to:

- Submission to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit Inquiry into the Management and Integrity of Electronic Information in the Commonwealth, National Office for the Information Economy, March 2003, <http://www.aph.gov.au/house/committee/jpaa/electronic_info/submissions/sub20.pdf>; and

- Management Advisory Committee, Government Use of Information and Communications Technology - ITAG Authentication Working Group sub-committee report - Appendix 5 - Authentication of external clients Working Group, Australian Public Service Commission, October 2002, <http://www.apsc.gov.au/mac/technology.pdf>.

[10] Refer to Accenture, eGovernment Leadership: Engaging the Customer, April 2003, <http://www.accenture.com/xd/xd.asp?it=enweb&xd=industries\government\gove_capa_egov.xml>.

[11] Committee on Authentication Technologies and their Privacy Implications, Who goes there? Authentication through the lens of privacy, , National Research Council of the National Academes, April 2003 (pre-publication version), at Recommendation 2.1 and 4.1.

[12] Above at Section 6.3.

[13] See IBM Corporation, Microsoft Corporation, BEA Systems, Inc., RSA Security, Inc., Verisign, Inc, Web Services Federation Language (WS-Federation), July 2003, < http://www-106.ibm.com/developerworks/library/ws-fed/>; and a joint whitepaper from IBM Corporation and Microsoft Corporation, Federation of Identities in a Web Services World, Version 1.0, July 2003, <http://msdn.microsoft.com/webservices/understanding/advancedwebservices/default.aspx?pull=/library/en-us/dnglobspec/html/ws-federation-strategy.asp>.

[14] <http://www.projectliberty.org>.

[15] <http://www.projectliberty.org/specs/>.

[16] <http://xml.coverpages.org/ni2003-04-15-b.html>.

[17] <http://zdnet.com.com/2100-1105-892838.html>.

[18] Liberty Alliance, Introduction to the Liberty Alliance Identity Architecture, Revision 1.0, March 2003, <http://www.projectliberty.org/resources/whitepapers/LAP Identity Architecture Whitepaper Final. PDF>, at p2.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Liberty Alliance, Report Finds Liberty Alliance Standard Helps Financial Institutions Extend Trusted Relationships and Enable New Online Businesses, Press Release, 9 July 2003, <http://xml.coverpages.org/FSTC-LibertySAMLReport.html>.

[21] For further discussion of Liberty and privacy see: Kaye, On Liberty and the Case for Anonymous Federation of Identity, RDS Strategies LLC September 2002, <http://www.rds.com/essays/20020904-liberty.html>; Loftesness, Jones, Critiquing a Liberty Alliance Critique, Glenbrook Partners, 2002, <http://www.glenbrook.com/opinions/liberty-critique.html>; and Migliore, Jupiter Raises Doubts About Passport, Liberty Alliance, Enterprise Systems, November 2001, <http://www.esj.com/news/article.asp?editorialsId=75>.

[23] Statement of Strategy 2003-2005, Department of Social and Family Affairs, 2002, <http://www.revenue.ie/pdf/sos03-05.pdf>.

[24] For more information about Reach's goals, objectives and actions see p 68 of Statement of Strategy 2003-2005, Department of Social and Family Affairs. Information about Ireland's eGovernment Agenda are on pp 40-2.

[25] See <http://www.reach.ie/about/what_is/standards.htm> for more information.

[26] See <http://www.reach.ie/about/what_is/coordination.htm> for more information.

[27] See <http://www.reach.ie/about/what_is/implementation.htm> for more information.

[28] <http://www.reach.ie/about/why_now/eGovernment.htm>.

[29] Commission of the European Communities, eEurope 2005: An information society for all, June 2002, <http://europa.eu.int/information_society/eeurope/2005/all_about/action_plan/index_en.htm>.

[30] Public Services Broker Phase 1 Requirements Statement, reachservices, July 2002, <http://www.reach.ie/publications/downloads/Requirements_Statement.pdf>.

[31] Ireland's eGovernment - Reach Services, ‘New Perspectives’, Irish Internet Association, November 2002, <http://newperspectives.iia.ie/e_article000109297.cfm>.

[32] Public Services Broker Phase 1 Requirements Statement, reachservices, July 2002, <http://www.reach.ie/publications/downloads/Requirements_Statement.pdf>, at p 4.

[33] Reach, Terms of Reference, May 2002, <http://www.reach.ie/archive.htm>.

[34] Ibid.

[35] <http://www.bailii.org/ie/legis/num_act/dpa1988168/>.

[36] <http://www.bailii.org/ie/legis/num_act/swa1998137/>.

[37] <http://www.bailii.org/ie/legis/num_act/1999/1999-3.html>.

[38] <http://www.bailii.org/ie/legis/num_act/swa2000137/>.

[39] <http://www.bailii.org/ie/legis/num_act/2002/2002-8.html>.

[40] <http://www.bailii.org/ie/legis/num_act/hoia1997339/>.

[41] <http://www.reach.ie/iams/>

[42] Refer to

- Clark, Hannifin acknowledges eGovernment delays, ElectricNews.net, 17 February 2003, <http://www.enn.ie/news.html?code=9350157>; and

- Irish eGovernment strategy experiencing delays to implementation, Interchange of Data between Administrators, 18 February 2003, <http://europa.eu.int/ISPO/ida/jsps/index.jsp?fuseAction=showDocument&documentID=875&parent=chapter&preChapterID=0-140-194-329-338>

for more information.

[43] Progress Update on the Public Services Broker, Press Release, Reach, 20 June 2003, <http://www.reach.ie/new.htm>.

[44] Ibid.

[45] <http://www.reachservices.ie/static/>.

[46] Above at note 37.

[47] <http://www.bailii.org/ie/legis/num_act/foia1997222/s1.html>.

[48] Above at notes 38-40.

[49] Department of Social, Community and Family Affairs, Establishment of National Framework for Integration of Public Services - ‘Reach’, August 1999, <http://www.cidb.ie/Live.nsf/0/4b45f6c7db25df87802567e6004dbf21?OpenDocument>.

[50] Data Protection with the Public Service Broker, Department of the Taoiseach, <http://www.agimo.gov.au/publications/2004/05/egovt_challenges/privacy/identity/brokered>.

[51] <http://www.reach.ie/about/achieve/privacy.htm>.

[52] Data Protection Essential for eGovernment plan, Irish Times, 9 September 2001, <http://www.cidb.ie/live.nsf/0/41b883a289b58c4880256b17005399e0?OpenDocument&ExpandSection=7>. See also <http://www.reach.ie/faqs.htm>, which notes the privacy protective features of the PSB scheme.

[53] <http://www.reach.ie/faqs.htm>.

[54] Privacy Fears on the Increase, warns Data Protection Commissioner, News Release, Data Protection Commissioner, 13 January 2003, <http://www.dataprivacy.ie/7nr130103.htm>.

[55] Refer to:

- McDonald, Privacy concerns balloon in Ireland, ElectricNews.net, 16 January 2003, <http://www.enn.ie/news.html?code=8894120>.

![[Privacy Impact Assessment (PIA) for Cooperative Intelligent Transport System (C-ITS) data messages]](/public/ssi/pubs/pub_3.png)

print this page

print this page sitemap

sitemap rss news feed

rss news feed manage email subscriptions

manage email subscriptions